How two POWs escaped in 1944 – and how their escape was reconstructed decades later

BY HANNE LESSAU AND TATIANA SZÉKELY

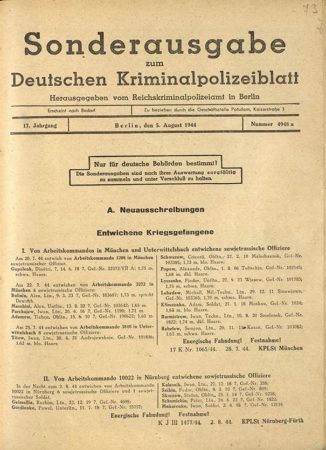

It all started with a “wanted” notice from 1944. A few months ago, while researching the history of the prisoner of war camp in Nuremberg-Langwasser, we came across a short report in a special supplement of a Nazi-era criminal police gazette, the Deutsches Kriminalpolizeiblatt. “Escaped Soviet officers from Work Crew 10022 in Nuremberg,” proclaimed the August 5, 1944, title page from the publication, in which security authorities regularly reported on escaped POWs so that officials throughout the Reich could identify and recapture them. The report listed names and prisoner numbers for seven Soviet POWs – along with the order for a “Vigorous manhunt. Arrest them.”

The Research Project „POWS in Nuremberg“

The “Bullet Order”: A criminal command to punish officers’ attempted escapes

It was not uncommon for prisoners of war to try to escape under the German Reich, even though most of the time they failed. There are no precise figures. Under the key governing agreement under international law, the Geneva Convention of 1929 – the Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War – trying to escape was not a crime, and “runaways” were vulnerable only to disciplinary punishment of a few days of more stringent arrest.

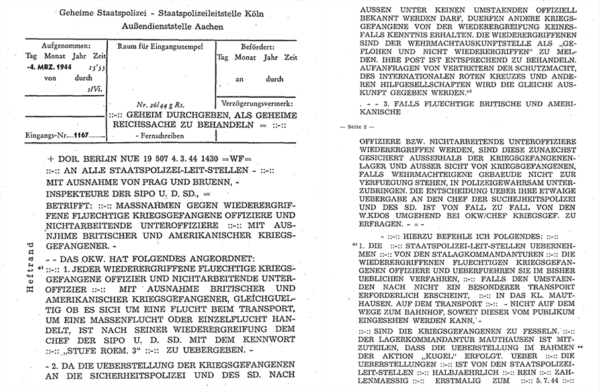

But in March 1944, Germany’s Secret State Police, the Gestapo – in coordination with the Wehrmacht – issued a criminal order. This Kugelerlass – the “Bullet Order” or “K-Befehl” – served as a legal excuse for a way of dealing with attempted escapees that would be applied from then on, in violation of international law. Gestapo head Heinrich Müller ordered that escaped officers who were reapprehended should be transferred to the Mauthausen concentration camp near Linz, and shot. Some 5,000 POWs were murdered at Mauthausen under this secret order in the months before the war ended. By far the largest group of “K prisoners” were Soviet officers, who accounted for 85 percent of those killed.

The first two pages of the surviving teletype of March 4, 1944 (published in full at https://www.uni-marburg.de/icwc/dateien/ntvol27.pdf, p. 424-428). The original “Bullet Order” itself has not survived.

This crime yet again demonstrates the brutal, inhuman handling of prisoners from the Soviet Union that had accompanied the German Wehrmacht’s “war of annihilation” ever since the German attack on Russia in June 1941. It meant that Soviet soldiers who tried to escape imprisonment were taking their lives in their hands. Even before the Bullet Order, recaptured members of the Red Army were transferred to concentration camps and murdered.

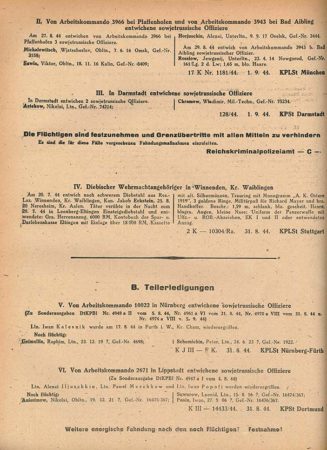

“Apprehended” – The unknown fate of five escapees

That knowledge compels us to read with different, alarmed eyes the August 5 report that six Soviet officers and one simple soldier had escaped from Nuremberg. What became of the men who tried to flee a few months after the Gestapo’s criminal order was issued? A search of later issues of the “wanted” gazette revealed that five of the “runaways” had been caught within a few weeks. The police gazette’s special supplement noted this as well, under the heading “Cases Partially Closed.” So far, we can only guess at what happened to the men after that. There is no documentation of their transfer to Mauthausen – not an unusual finding. But the search goes on.

We would welcome reports from anyone who has information about the fates of

– Pavel Gordienko, Sublieutenant, born July 11, 1918, prisoner no. 55757

– Ivan Kalesnik, Lieutenant, born December 27, 1918, prisoner no. 358

– Fyodor Seikin, First Lieutenant, born February 8, 1910, prisoner no. 809

– Stefan Skorzov, First Lieutenant, Born January 23, 1914, prisoner no. 9238

– Ivan Makarenko, Soldier, born April 2, 1918, prisoner no. 12118

Please contact us at

prisoners-of-war@stadt.nuernberg.de

“Still at large.” Could two officers really have escaped?

Nevertheless, by September 9, 1944, two officers were still at large: Rakhim Gaynulin and Petr Shumichin. The police gazette makes no further mention of their names up to the war’s end. Could they really have escaped?

Months after we thought our research had ended, a happy coincidence brought us back to the story of this escape with new information, and enabled us to find out what had become of the two men. A Berlin association, KONTAKTE-KOHTAKTbI e.V., which has been working admirably for years to preserve the memory of Soviet prisoners of war, sent us a dozen letters in which former prisoners of war reported on their time in Nuremberg. And among them was a letter from one Petr Lazarevitch Shumichin.

The writer reported about his family, about growing up, and that after nine years of school he had joined the army because of the war. Descriptions of his capture followed – together with a first clue that he might have been one of the escapees: in 1943, he said, he had been taken deep into the Reich, to Nuremberg. At first he was at a large POW camp – Langwasser – and later in a work crew at the “iron works.”

A 2009 letter from Petr Shumichin

Many years after his capture, Petr Shumichin still recalled with horror the air raids that struck the barracks camp a number of times in 1943 and 1944. His memories of the subsequent missions to clear rubble and recover corpses were no less vivid. “I thought all the time about how I might escape from there, also about which comrades I could enlist in my plan so I wouldn’t have to escape alone.” Someone recommended Rakhim Zainulovitch Gaynulin, another native of Siberia. Resourceful support from a German worker at the “iron works” helped them assemble the necessary tools for their escape – “a compass, a crowbar, and a map” – and the daredevil exploit began. They had fastened rubber soles under their shoes to keep dogs from picking up their tracks. They traveled only at night, and unlike the other five escapees, “we headed farther south, and then later east. The first city we reached was Amberg, and then Plzen – those were small cities – and finally Czechia – Prague – and Slovakia – Námestovo. We survived the whole time from what we could lay our hands on: ears of wheat, rye, corn, wild apples, pears and other things.” They traveled for four months until they crossed paths with a group of partisans in the Carpathians. These they joined and fought beside until they could rejoin the Red Army.

That information, the name of Rakhim Gaynulin as his companion, and his prisoner number 1822 – the same number that was in the “wanted” notice – made the identification definite. The letter was indeed from one of the men who had escaped in August 1944.

A first glimpse of life before the war

Petr Shumichin’s letter provided a great deal of information that offered a foothold for further research: his birthplace, his detachment to the “iron works,” his address in 2009. Could we find out more, from official or private sources, about his life and that of his companion in the escape? Could this improbable story of a successful 1944 escape by two Soviet prisoners of war yield materials that we might be able to put on display in the exhibition planned for May 2019 here at the Documentation Center?

The search began. A first inquiry went to the Central Archive of the Ministry of Defense in Podolsk, which keeps the Soviet Army’s “Officers’ File.” The personnel cards for both men showed up, including important information about their lives until the war ended – some of which was already available from the letter, but some of it also new. Petr Shumichin, we now knew, was born in the summer of 1923 in the Altai Republic, and came from a family of workers. He was wounded on October 6, 1942, near the town of Zubtsovo, and had been taken prisoner. After an extended stay in a military hospital, he was transported to Nuremberg early in 1943. Rakhim Gaynulin had also survived his escape and the war. He was four years older than his companion, and came from a family of farmers living in Western Siberia. After completing lower school, he attended the Pedagogical Teaching Institute in Tomsk. He was drafted into the Red Army in 1939, and was taken prisoner in the battle for Liepaja, in Latvia, in July 1941, a few weeks after the German army attacked.

Searching for the families

By the time the information arrived from the defense archive, we had also made progress on other fronts. The Internet had turned up a photo of Petr Shumichin’s gravestone – he had died in 2011 – and also a contact with a nephew. Social media had then given us leads on Rakhim Gaynulin’s family. As we gradually discovered, the two men had stayed in touch after their escape, and had become friends. The two former POWs’ families still know each other.

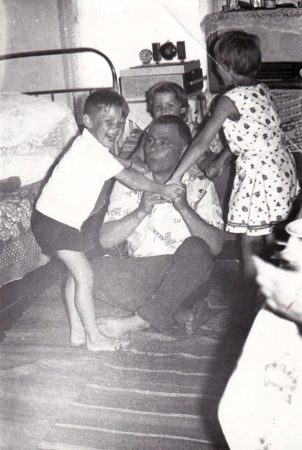

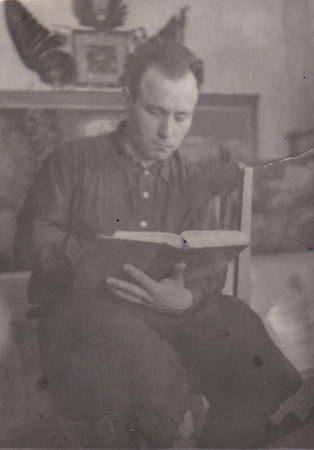

A touching gesture

We made contact with the two men’s families by email and telephone, explaining our interest in their parents’ story. Then, just a few days ago, we received dozens of personal photos showing Petr Shumichin and Rakhim Gaynulin among their families, as veterans of World War II or teaching in a classroom. We also learned more about what happened to them after the war. The returnees had to undergo an intensive inquiry, and like many former prisoners of war, were forced to defend themselves against charges of having collaborated with the Germans. While Rakhim Gaynulin was allowed to return to his former home and establish a family shortly after the inquiry, Shumichin would not be able to return to his home region for seven years. Rakhim Gaynulin resumed his prewar profession, and quickly went back to work as a teacher in his home district – in 1962 he became the director of various general educational schools. But his comrade Petr Shumichin had to do forced labor into the 1950s – now in Stalin’s Gulag camps. After returning to his home region, he earned a living working in a mine. He married Anastasia Timofeevna, and they had three daughters and a son.

It was a touching gesture: that a family would allow an unknown institution hundreds of kilometers away, in the very city where their father or grandfather had suffered, to have a look at the family album. The photos of Petr Shumichin and Rakhim Gaynulin will now be stored here at the Documentation Center and used in historical communications work. But at the same time, they bear double witness to an amazing story: the tale of the successful escape of two Soviet officers from Nuremberg in the late summer of 1944, and its successful reconstruction 74 years later.

Hanne Lessau is a historian at the Documentation Center Nazi Party Rally Grounds, and heads the project “The Nazi Party Rally Grounds during the War.”

Tatiana Székely researches the lives of Soviet prisoners of war in Nuremberg as part of the project.