Deutsch | Italiano | Polski | Русский

Uncovering the past at the Nuremberg-Langwasser POW camp

BY HANNE LESSAU

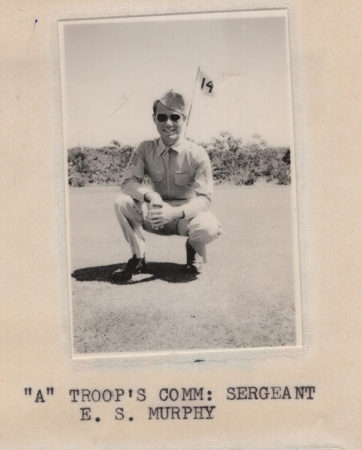

Eugene Murphy at the Langwasser prisoner of war camp

On the day after Christmas 1944, Eugene Murphy and hundreds of other US soldiers reached the prisoner of war camp in Langwasser. It had been a harrowing journey. Ten days before, Murphy and many others in his reconnaissance unit had been captured in Belgium’s Ardennes region during the Battle of the Bulge, Germany’s last major offensive of the western war. Since then, on foot and by train, they had been taken deep into the German Reich. On their arrival in Langwasser, the Americans were sent to a separate block, with about 100 of them in each of the wooden barracks. Years later, Murphy could still recall the unbearable cold, the meager food rations, and the British air raid on Nuremberg that he endured as a POW in Langwasser on January 2, 1945. His American comrades liberated him in late April.

US reconnaissance soldier Eugene Murphy. Photo credit: Ryan Barr

Researching the camp on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds

We know about Eugene Murphy because last winter, members of his family came to Nuremberg to see where their relative had suffered his wartime ordeal: the site of the former POW camp in Nuremberg-Langwasser. While here, they presented the Documentation Center at the Nazi Party Rally Grounds with photos and a memoir that Murphy had written. He had been just one of some 200,000 people – a number of them from the United States but most from Southern, Eastern, and Western Europe – who were interned at the Langwasser camp during the Second World War. The complex opened in 1939, only a few days after the war began, at the former SA camp on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds – a site that had housed tens of thousands of party members just a few years before.

- Nazi Party members camping in tents at Langwasser, 1936. Photo credit: Documentation Center Nazi Party Rally Grounds

- Polish POWS at Stalag XIII A in Nuremberg-Langwasser, 1939/40. Photo credit: Erlangen Municipal Archives, Rühl Collection

People often contact the Documentation Center to find out about family members who were confined at Langwasser. But until recently the extensive camp complex, which stood on the Rally Grounds from 1939 to 1945, was not a main theme in the Documentation Center’s work, and the Center has no items relating to the camp in its collection. To fill this gap, since 2017 we have been pursuing an international research project to study the close involvement of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds in the Nazi regime’s racially motivated, criminal wartime practices and policies.

Focusing on prisoners’ personal stories and perspectives

We feel it is especially important to reconstruct the stories of individuals, and also to get an understanding of how the camp was experienced by those who were interned there. That’s why the photos from Eugene Murphy’s collection are so valuable. Some of the soldiers in his reconnaissance unit were able to take personal photos in the camp. Those photos, like the one at the top of this article or the ones below from inside a barrack, offer an insider’s glimpse of life at Langwasser. So far, these are the only known pictures of their kind from the camp.

Photos from inside the barracks, with captions. (The upper photo shows soldiers surreptitiously listening to the news, an activity Murphy also describes in his memoirs.) Photo credit: Ryan Barr

With most of the former prisoners now deceased, this effort comes late – but not too late to uncover the stories of individuals. In recent decades, other institutions have collected private materials and interviewed eyewitnesses, including some who were in camps on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds during the war. But the most active investigators have been family members combing through online forums for information about their interned relatives.

The anguish of Soviet prisoners of war

The amount of material available about individual prisoners varies greatly and depends heavily on their nationality, on when they were interned at Nuremberg, and on their military rank. For example, French officers, who were treated humanely, have left a considerable quantity of personal photos, drawings, and memoirs about Nuremberg. Yet it’s rare to find so much as a single personal photo of one of the ten thousand Soviet POWs at Langwasser.

Of the more than 5 million Red Army soldiers captured by the Germans during their war of annihilation against the Soviet Union, over 60 percent died. This mass death from malnutrition, disease, and exhaustion was a deliberate tactic in the Nazi regime’s brutal conduct of the war. Soviet POWs were not allowed to write or receive letters, were barred from aid organizations’ assistance, and had to fight for survival under catastrophic conditions. Many families spent decades not knowing what had become of their loved ones.

The all-too-brief life of Vasily Ismailov from Tula (Russia)

- Personal photos of Vasily Ismailov with his family,

- late 1930s. Photo credit: Felix Ismailov

Vasily Ismailov was 30 years old, a trained telecommunications engineer and the married father of two daughters, when he was captured at Stalingrad. He was brought to Franconia early on, in the fall of 1942, and then put to forced labor. He and about 100 other Soviet officers had the job of clearing the streets after air raids and digging bomb shelters. By 1943 he had already fallen seriously ill, and spent three months in the POW reserve hospital at the Langwasser camp. A second hospitalization, in November 1944, proved fatal; he died at the end of the month and was buried in the Südfriedhof cemetery. His family learned of his fate only a few years ago – thanks to years of investigation by Vasily’s grandson Felix. Felix Ismailov, accompanied by other relatives, visited Vasily’s grave for the first time in 2011. They decorated the gravesite with flowers, bread, and photos and commemorated their visit in numerous photos, videos, and albums.

- Felix Ismailov at the Südfriedhof cemetery, where his grandfather is interred in a mass grave with other Soviet prisoners of war.

- A page from the album commemorating the family’s visit to the gravesite. Photo credit: Felix Ismailov

This example, like Eugene Murphy’s relatives’ visit to Langwasser, gives a sense of how important descendants feel it is to learn about their family members’ internment and to be able to visit the place where they endured so much. One more reason why it’s so important to the Documentation Center to keep the stories of Langwasser’s prisoners from being forgotten. You can help us in our work if you have any information or documents about POWs interned at Nuremberg-Langwasser or who were forced laborers in Nuremberg during the Second World War, or if you know anyone seeking information about relatives who were prisoners at the Nuremberg-Langwasser POW camp. You can reach us by phone at +49 911 408 70 274 or by email at prisoners-of-war@stadt.nuernberg.de. We warmly welcome your feedback.

Article “How two POWs escaped in 1944”

Hanne Lessau is a historian at the Documentation Center Nazi Party Rally Grounds, and heads the project “The Nazi Party Rally Grounds during the War.”

Cover photo: Soldiers walking in the American block of the Langwasser camp, spring 1945. Photo credit: Ryan Barr